Distinguished evolutionist Michael Ghiselin asked, “What does evolution teach us about human nature?” His answer: “It teaches us that human nature is a superstition.”

Variability in all parts of all species is a primary fact of nature according to Darwinian evolution, and this ubiquitous variation is the fuel that powers natural selection. It is the conviction, inherited from Darwin, that species vary in all respects at any moment in time, and that natural selection causes those species to change in profound ways over time, that has made the likes of Ghiselin so skeptical of the thought that species have “natures”. Evolutionists are united in their rejection of “human nature”.

What exactly makes us human? Do Homo sapiens share a common essence or nature? When we are born, what do we show up with? Are we fundamentally created in the image of God or the result of the evolutionary process of natural selection? Are we innately selfish and competitive or altruistic and cooperative?

The way we perceive human nature today is still influenced by assumptions from the Medieval Christian world view (human nature as fallen, depraved, and flawed) and the Age of Enlightenment (human nature as inherently good and capable of continuous improvement through reason and education). Consequently, much of humanity behaves according to these assumptions, and both pessimistic and optimistic view of human nature has its problems.

Human beings are the most compassionate, most violent, most creative, and most destructive of all animals.

In my view, we have an outdated, unhelpful and at times disastrous view of “human nature” and I plan on writing about this in a series of upcoming articles.

This past week I was investigating the discussion around what constitutes the foundational components we are born with as human beings. At risk of oversimplifying the matter, there are two primary camps: blank slate and innatism.

This theory states that human beings are born empty of any built-in or innate mental content and that all knowledge and beliefs are acquired through experience and sensory perception.

In Western philosophy, the concept of tabula rasa can be traced back to the writings of Aristotle who writes in his treatise De Anima (On the Soul) of the “unscribed tablet.” In one of the more well-known passages of this treatise, he writes that:

“Haven’t we already disposed of the difficulty about interaction involving a common element, when we said that mind is in a sense potentially whatever is thinkable, though actually it is nothing until it has thought? What it thinks must be in it just as characters may be said to be on a writing tablet on which as yet nothing stands written: this is exactly what happens with mind.”

If your interested in exploring these ideas further, you might read, The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature by Steven Pinker.

Innatism, on the other hand, the view that the mind is born with already-formed ideas, knowledge, and beliefs. Innatism states that although individual human beings vary in many ways (culturally, ethnically, linguistically, and so on), innate ideas are the same for everyone everywhere. For example, Plato argues that if there are certain concepts that we know to be true but did not learn from experience, then it must be because we have an innate knowledge of it and that this knowledge must have been gained before birth. If you want to investigate innatism further, a useful book is, Inborn Knowledge: The Mystery Within.

Noam Chomsky asserted a form of innatism in his theory that humans are born with an innate capacity for language, a concept known as Universal Grammar. This innate ability, housed in the brain’s Language Acquisition Device (LAD), allows children to acquire language without explicit instruction and to grasp complex grammatical rules that go beyond what they are explicitly taught.

The blank slate vs innatism discussion relates to the conflict between rationalists (who believe certain ideas exist independently of experience) and empiricists (who believe knowledge is derived from experience).

It would be wrong to imply that blank slate vs innatism is an either/or proposition. For example, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins views lean towards rejecting the “blank slate” or “tabula rasa” concept in favor of a more nuanced understanding of human nature that acknowledges innate predispositions. While not strictly an “innatist” in the philosophical sense, his work emphasizes the role of genetics and evolutionary biology in shaping behavior and cognition, suggesting that humans are not born with completely empty minds.

These discussions also prompt the nature vs nurture conversation, which is a long-standing discussion about the relative importance of inherited (nature) and environmental (nurture) factors in shaping an individual's traits and behaviors. While it was once framed as an either/or proposition, modern science recognizes that both nature and nurture play significant roles and interact with each other.

All these above ideas might jog your memory of Jean-Paul Sartre’s assertion that “existence precedes essence”. This is a central concept in existentialist philosophy, popularized by Sartre. It states that humans first exist, and then through their actions and choices, they define their own essence or nature, rather than having a predetermined essence before they exist. This idea contrasts with traditional philosophical views where essence is seen as preceding existence.

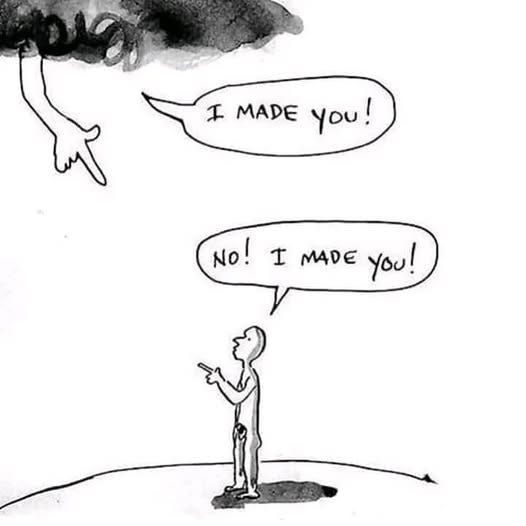

The philosopher René Descartes theorized that knowledge of God is innate in everybody, and assumed that God or a similar being or process placed innate ideas and principles in the human mind.

Religion has its own ideas about what comes with the birth of every human being. The imago Dei, concept associated with the monotheistic religions assert, asserts that human beings are created in the “image of God”.

The exact meaning of the phrase has been debated for millennia. Jewish philosopher Philo, argued that being made in the image of God does not mean that God possesses human-like features, but rather the reverse: that the statement is figurative language for God bestowing special honor unto humankind, which he did not confer unto the rest of creation.

The history of the Christian interpretation of the “image of God” has primarily included three central streams of thought:

the “image of God” exists in shared characteristics between God and humanity such as rationality or morality

a relational understanding argues that the image is found in human relationships with God and each other

image of God serves as a role or function whereby humans act on God’s behalf and serve to represent God in the created order

Of course all these iterations of the “image of God” are tied to a theistic view of God, which in my view is the least defensible view of “God”. If you are a Pantheist or Panentheist, you’d have to work out these ideas differently.

For example, with respect to Pantheism, instead of a personal, separate God creating humanity in His image, pantheism posits that humanity, and everything else, is part of the divine. This means there's no distinct image of God in the anthropomorphic sense, but rather, humanity and the universe are expressions of the divine. Likewise in Panentheism, it suggests that humanity’s capacity for relationship, creativity, and moral choice reflects God's own nature and activity within the universe.

Ludwig Feuerbach, a 19th century German philosopher, stands out for his radical interpretation of the divine. Through his seminal work The Essence of Christianity, Feuerbach famously argued that God is a projection of human nature, not the other way around. In his view, religious concepts, including the idea of God, are essentially anthropomorphisms, meaning they are human-created representations of human ideals and desires projected onto a divine being.

The topic of “God” is not the focus of this article. I published several articles on the topic of God that you can check out if you’re interested, including:

Don't Throw the Baby Out With the Bathwater (or should you?)

Unbeliever: The Post-Religion Move to Agnosticism and Atheism

The doctrine of “imago Dei” (“image of God”) is a foundational concept in Christian ethics that serves as a basis for morality. It suggests that humans, created in God's image, possess inherent dignity and value, prompting ethical behavior and respect for all people.

A non-religious understanding of morality views natural selection, the driving force behind evolution, as playing a significant role in shaping the development of morality in humans. The idea is that natural selection favored traits and behaviors that promote social cohesion and cooperation within groups, which are fundamental to the development of moral systems. A few useful books on the subject are:

The Moral Animal: Why We Are, the Way We Are: The New Science of Evolutionary Psychology by Robert Wright

Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst by Robert M. Sapolsky

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari

The Original Sin Problem

There is a toxic innatism that I find in traditional Christian dogma, namely the “original sin” or “total depravity” doctrine, which essentially add up to the idea that every human being is inherently corrupt and incapable of choosing good on their own.

Christian thinking essentially argues the reverse of the existential philosophers by asserting that “essence precedes existence”. But our “essence”, according to traditional Christian theology, is a contradictory message. One’s “essence” is anchored in being created in the “image of God” but that image and essence has been corrupted by sin and every human being is born in a depraved state. This depraved state runs the show and ultimately leads to an afterlife of eternal conscious torment in Hell, unless it is remedied by the Christian salvation formula. By the way, I wrote an extensive articles previously on the doctrines of original sin, repentance theology and Hell.

In my view, the Christian religion is obsessed with “sin”. Its entire message revolves around it. It proclaims a sin-management gospel. According to this view, the core identity of every human being is “sinner,” and the significance of Jesus is fixing it.

It has always been curious to me that the cornerstone of this version of “the gospel” is that humankind is born bad, which misses the original divine declaration of humankind as good. Unfortunately, the Christian religion is insistent and inventive in keeping people focused on the issue of sin.

The notion of original sin is a creation of the church. It asserts that all human beings are born with a sin nature as a result of Adam and Eve’s rebellion against God in Eden. According to the doctrine, humanity shares in Adam and Eve’s sin, transmitted by human generation.

The Christian concept of original sin was first mentioned by Church fathers such as Irenaeous and Augustine in the 2nd century. The issue needing resolved was: How could sin have entered the world if God is good? Answer: Adam and Eve’s disobedience and subsequently the entire human race, their offspring.

To believe in the doctrine of original sin you would have to believe a few absurd things. You’d first have to believe that the Bible’s creation story is to be taken literally – that there was an actual Adam and Eve who were the first human beings, and that the family tree of all humankind is traced back to them. You’d also have to believe that Adam and Eve’s act of disobedience and rebellion against God resulted in a sinful condition that can be propagated through human conception and birth.

The doctrine of original sin posed as many problems as it solved. How could Jesus be God, as Christianity claimed, if he was born a human? Hence the doctrine of the virgin birth – the belief that Mary was not impregnated through the sperm of Joseph, which would have been contaminated by the sinful condition, but impregnated directly by God himself.

The Catholic Church takes it a step further with the teaching of the Immaculate Conception, which asserts that Mary was conceived by normal biological means, but God acted upon her soul, keeping her “immaculate,” at the time of her own conception.

A further complication of the original sin doctrine is the question of how one can believe and appropriate God’s remedy of Jesus if our natural fallen state is one of rebellion. Hence the doctrine of “regeneration,” which states that God first changes the sinner’s nature to make it possible for them to repent.

Repentance and conversion both follow regeneration because the sinner cannot naturally obey God's command to repent and be converted unless and until God alters his nature. Don’t feel badly if all this starts to feel a bit convoluted. In divinity school I learned how to become a theological contortionist – stretching, bending, twisting and beating doctrines into submission until they somehow managed to hold several absurd notions together, if only hanging by a thread.

The Bible itself is contradictory when it comes to the matter of original sin, and there is no consistent or coherent message about it. The Apostle Paul wrote that “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God,” and yet Jesus himself said, “blessed are the pure in heart,” implying that one’s innermost being is untainted. Even in the Genesis creation story, prior to the fall of Adam and Eve, God’s original pronouncement upon all creation, including the human person, is that they are “good.”

The doctrine of original sin is problematic from every feasible angle of a reasonably thinking person. So the question is, why do so many people believe it? People once believed the world was flat and the earth was the center of the universe, but once they were given more accurate information they eventually adopted the new view. And yet, people hold onto religious beliefs despite their absurdity and the absence of evidence.

Religious truth is often held to a different standard. It gets a pass in terms of how we typically determine the truth of a proposition. When a religious belief appears unfounded or illogical, we often hear the phrase, “God’s ways are not our ways.” It’s considered the height of arrogance to think one can comprehend the ways of God with the human mind. After all, God is “omniscient” or all-knowing.

Insert the carrot and the stick. Let’s say you believe there is a God who rewards and punishes people, and that your eternal future of heaven or hell are hanging in the balance. If the authoritative people (clergy, Bible scholars) impart a set of beliefs you’re expected to uphold to remain in good standing with God, then you could be persuaded to accept in any number of absurd things. The alternative would be to question them, jeopardizing your standing with the Almighty. So the short answer to why people who should know better believe nonsensical religious ideas is fear.

In my view, the doctrine of original sin is false. Religion created a problem that doesn’t exist to establish itself as the cure and keep itself in business.

Many religions teach that human beings are born sinners and need to be saved to be good. Consider the possibility that this view abdicates personal responsibility. First, it implies that our misdeeds in the world are inevitable because they are a product of our flawed condition. Secondly, it puts the onus on an outside savior to fix it.

Here’s an alternative mindset:

I was born a human being.

I have the capacity to be an instrument of goodness or corruption in the world.

I am responsible for my actions and their consequences.

My life experiences have wounded me in ways that contribute to the harmful things I do to myself, others and the planet.

I can take responsibility for who I am being in the world by addressing the root cause of my destructive and harmful mindsets and actions.

I am not perfect and never will be, but I can make a determined effort each day to tend to my liberation and wholeness.

I may face times or situations when I need help, and I will seek the help I need.

Even on the best days I will stumble and see ways I messed up, but I will offer acceptance, patience and compassion to myself, knowing that self-love and not self-condemnation will aid my growth and wholeness.

I accept that all human beings are in the same boat I'm in, and I will be ready to offer compassion to others in their challenges and struggles to be the best human being they can be.

Rethinking Eve

Eve was the hero. Never forget that.

I think we got the whole Eve and fall-of-humankind story all wrong. In the Genesis story, commonly referred to as "the Fall," I see it much differently from the traditional Christian interpretation. Firstly, I believe the story was meant to be taken figuratively or allegorically, not literally.

The story contains several themes worth considering.

In my view, Eve is the daring and courageous one. God said don't eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. She did it anyway. Why?

Let's digress momentarily to consider the context here. If the Bible was a carefully crafted and plotted propagandist document to perpetuate a positive theism, it failed miserably. The picture it presents of God is one who is complicated, contradictory, capricious, and at times, evil.

Why would God put the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil in the Garden, knowing full well that Adam and Eve would do the very thing he told them not to? Put a bunch of people in a room with two windows and say to them, whatever you do just don't look through the window on the right. What do you think they will all do? They will do exactly that.

Why would God risk the well-being of his entire created order by telling Adam and Eve not to do something he knew they would? The way the story is framed, regardless of the role of the serpent, God is ultimately responsible and the one to blame for "the Fall." You can't set a building on fire and deny culpability when it burns to the ground.

In my mind, Eve is the hero in the story. God said don't eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. She did. The world often makes its greatest advances by disobedient people who break the rules. Oscar Wilde wrote, “Disobedience is man's original virtue.” Except it was a woman and it was Eve. She was the was first rule-breaker, and we should honor her for this.

In the story, God tells Adam and Eve not to eat the fruit. However, they never promise they won't. Should they have been obedient? How obedient do you want your children to be? Or course you want them to operate with prudence and integrity. However, you also want them to be disobedient enough to go into the world and act with conviction and even defiance. Some rules are meant to be and should be broken.

Little girls are often told they should be proper, accommodating and nice. Historian, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich wrote, “Well-behaved women seldom make history.” In Eve's case, she did humankind an epic favor by risking disobedience.

Eve's decision made complete sense. According to the text, Eve chose to eat the fruit from the forbidden tree because:

It was necessary for sustenance - it was “good for food”

It resonated with her aesthetic sensibilities - it was “pleasing to the eye”

It would contribute to her growth and maturity - “desirable for gaining wisdom.”

If I came to you and said, “I want to offer you something - it’s necessary to live, pleasing and satisfying, and will transform your entire way of being in the world. Are you interested?” My guess is that you would say, “Yes!” In addition to all that, Eve didn’t selfishly claim it all for herself. She shared the fruit with her sidekick, Adam.

Meanwhile, notice that even though Adam didn’t have the moxie to break the rules and risk taking the fruit himself, he had no problem gladly accepting it from Eve. And yet, Adam blames both God and Eve for the whole ordeal. Adam says, “The woman YOU PUT HERE with me—SHE gave me some fruit from the tree...” In the story, Adam plays the victim card and throws his partner under the bus to save his ass, which is quite unbecoming and disgracing.

Eve also did an epic deflection by telling God, “The serpent made me do it.” She has a point though; that serpent was quite crafty.

I wish the story read differently and Eve had said to God:

“Okay, God. Here's the deal. Yes, I did it. I know you said not to eat from that tree. You also gave me a brain to use and I used it. I never promised I wouldn't. I was feeling it. So, I went for it. I put on my big-girl panties and ate the fruit. I didn't mean any disrespect to you. I was doing me. Actions have consequences. I get that now. Lesson learned.”

Taking this account metaphorically, I think the idea was to construct a story that sets up the complexities of properly executing our freedom and agency in the world. God’s command not to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is depicted as a safeguard to protect Adam and Eve from shouldering too heavy a burden of understanding the world and life in its most transparent terms. In other words, to know the world, particularly in its most frightening potentialities and possibilities, in which only God was capable of seeing. After eating the fruit we are told their eyes were opened, which means God initially had blinders on them so they were not capable of seeing the whole deal.

The knowledge of good and evil can be seen in the story in two ways. On the one hand, you might say that ignorance is bliss. Not having this knowledge was a feature of the paradise and harmony that was depicted prior to eating the forbidden fruit/knowledge. On the other hand, Eve saw that eating the fruit would be “gaining wisdom.” In other words, it’s best to know what the reality truly is so you know how to respond accordingly. In this sense, it should be noted that Eve was the one who chose to gain the knowledge of of the givens of human existence, which in my view is human immortality, human groundlessness, and human insatiability. I discuss this in my article, The Rules of the Game.

The story of Adam and Eve and the forbidden fruit is not about the coming of sin into the world, but the emergence of self-consciousness, and confronting the realities of the human situation. With knowledge comes responsibility. Human freedom and responsibility can be a frightening responsibility. Jean-Paul Sartre wrote,

“Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does. It is up to you to give life a meaning.”

Sartre’s point is that human beings are fundamentally free to make their own choices and are responsible for the outcomes, but this freedom can be a burden and source of anguish. We cannot rely on external factors, like God or pre-determined societal norms, to justify our actions or choices. We are solely responsible for our lives. This radical freedom can be discomforting, as it requires us to constantly confront the possibilities and consequences of our choices. There is no one to tell us what is right or wrong, and we must bear the weight of creating our own values and meaning.

Eve took all the risks in Bible story. It cost her - she lost something, she gained something. It’s not easy living responsibly with the things we know. What we learn from Eve is that any paradise based upon ignorance or half the truth, is fool's gold.

Eve’s disobedience is not what corrupted the human species, but is an invitation and challenge to lean into the totality of the lived human experience... even if it requires defiance against the voices that tell us what we can or cannot do. Speaking of defiant and heroic women, it was Simone de Beauvoir wrote, “It is in the knowledge of the genuine conditions of our lives that we must draw our strength to live and our reasons for living.”

For Consideration

The central question this article points to is: What are you born with? For example:

Were you born a blank slate to be shaped by life experience, or born with already-formed knowledge?

Were you born into an existence with a structure for morality and ethics based upon absolute truth, or born into a world where you are solely responsible for your meaning, values and choices?

Were you born with an innate sin-condition that needs religious salvation to resolve, or were you born with the capacity for both constructive or destructive mindsets and behavior that you are responsible for managing?

If there’s a quantifiable “human nature”, there will always be debate about what is included in it. Generally, the term “human nature” refers to the fundamental dispositions and characteristics that are said to be naturally present in humans. As stated, many believe humans share certain fundamental characteristics, behaviors, and ways of thinking, while others argue that human behavior is primarily shaped by culture and environment.

“Essentialism”, when applied to Homo sapiens, suggests that humans possess inherent, unchanging characteristics that define them as a species. This view is often contrasted with non-essentialist perspectives, which emphasize the variability and fluidity of human nature, influenced by culture, environment, and individual experience.

Essentialism posits that humans have a core essence, a set of properties that are necessary and sufficient for being human. These defining properties are considered intrinsic to humans and not subject to change by external factors or experiences.

Examples of essentialist claims about human nature:

Rationality:

Humans are inherently rational beings, capable of reason and logical thought.

Sociality:

Humans are inherently social creatures, needing to live and interact with others.

Language:

Language is a uniquely human capacity that defines our nature and allows for complex communication.

It seems obvious that humans share a common biology and many fundamental psychological traits, such as the capacity for language, social interaction, and emotional expression. Despite cultural differences, there are striking similarities in human behavior and social structures across different societies. The evolutionary perspective asserts that evolution has shaped humans with certain predispositions and tendencies that contribute to what we might call human nature.

If you consider the “no-self” teaching of Eastern spirituality or the ideas inherent in process philosophy that each of us are “occasions” or “becomings” in a field of relationality, it adds a different dimension for exploring what we are.

I’d be interested in your thoughts on this subject and the themes discussed in this article.

I sometimes feel like self-help culture, personal development and even spiritual growth, overcomplicates the process of cultivating a life of well-being, meaning and purpose. If you were to take an “essentialist” approach to cultivating a more profound human life, you might look at those three areas mentioned above: rationality, sociality and language.

A way to approach these might be:

Utilizing our powers of rationality and reasoning to identify the values to guide our way of being in the world, and what it means to live life meaningfully.

Developing, deepening and embodying our nature of sociality by learning to be with the world and all its relationality in interpersonal, intersocietal and interplanetary relationships.

Becoming more responsible and regenerative with our use of language in our speaking and writing, and the power of language to shape the world.

In Summary

Discussions about blank slate vs innatism or nature vs nurture shouldn’t be reduced to an either/or option.

The traditional religious view on human nature is confusing and contradictory: Is it imago Dei or total depravity, are we born good or bad, should we celebrate what we are or do we need saved from ourselves?

Existence precedes essence” states that humans first exist, and then through their actions and choices, they define their own essence or nature, rather than having a predetermined essence before they exist.

Self-help culture, personal development and even spiritual growth, can overcomplicate the process of cultivating a life of well-being, meaning and purpose.

Never forget that Eve was the hero.

Deconstructionology is a subscriber-supported labor of love. If you find what I share meaningful, please consider becoming a paid subscriber at $5 a month or $50 annually, and recommending Deconstructionology to others. As a token of my appreciation I offer several perks and exclusive benefits. Thank you :)

“Every step we take on earth brings us to a new world.”

- Federico Garcia Lorca

There’s a lot in here that lands hard, especially the part about Eve. Not as the villain, but as the first human to lean into freedom, agency, and consequence. That flips the whole narrative, and it deserves to be flipped. She didn’t fall. She woke up.

The idea of human nature has been so loaded with religious baggage and binary thinking. Are we blank slates or preloaded sinners? Divine or depraved? But maybe what we’re born with is potential. Not some fixed essence, but the raw material for becoming. Evolutionary science and existentialist philosophy actually meet here. They both point to the same truth: who we are is shaped in relationship, through choice and reflection.

What has always disturbed me about the doctrine of original sin isn’t just the shame it instills. It’s the way it encourages people to stay passive. If you’re born bad and can’t choose good without outside intervention, then you’re off the hook. Someone else has to fix you. That’s a great business model for religion, but a terrible framework for personal responsibility.

This piece is a solid reminder that we’re not born broken. We’re born capable. And what we do with that capacity is what defines us.

The story of Adam and Eve originated with the Mesopotamians. It was handed down by oral tradition over many generations. We all know how a story can change over time, when passed down by word of mouth.

The part of the story that seems to be missing is about how Adam and Eve lost their innocence. Was it from eating forbidden fruit, or did it come from the realization that you are no longer a child. You become an adult. With that, you become responsible for your actions. Children can be excused because they lack maturity and understanding. Adults don't get that free pass.