I’m starting a new series today for paid subscribers: “The Case for Unifying Science and Religion”. In last week’s Week in Review I tipped my hand that for some time now I’ve been exploring science as a permittable pathway for deep spiritual meaning.

The discovery of Hegel’s dialectic, a philosophical concept attributed to Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, which describes a framework for resolving seemingly opposing and irreconcilable ideas by creating a synergistic alternative. It’s often explained as: Thesis → Antithesis → Synthesis. I have used this concept recently in exploring the synergistic significance of joining Christianity and Atheism, which appear on the surface to be incompatible opposites. In my view, Hegel’s dialectic may be capable of reconciling the age-old schism between religion and science.

The prevailing view of science is “scientific naturalism”, which states that nothing exists beyond the natural world and that scientific forms of investigation are the only way to gain knowledge of the cosmos. This view eliminates any possibility of a supernatural world - no gods, no spirits, no transcendent meanings in the fundamental architecture of the world.

On the other hand, the below explanation of the universe doesn’t exactly inspire a life of beauty, transcendence and meaning:

I’m not saying that religion and spirituality are legitimate on the basis of being inserted into our understanding of the universe as a coping mechanism for the cold hard facts of existence. In other words, that the use of religion and spirituality are merely to help the medicine go down. No, what I’m arguing in this series is that religion and spirituality (when understood a certain way) has something invaluable to offer alongside science in constructing the narrative of existence.

In my view, Hegel’s dialectic is useful for reconciling the schism between science and religion. In this respect, one could apply the Hegel dialectic as follows:

Thesis: The proper understanding of life can only be attained through science.

Antithesis: Life cannot be truly understood without the belief in God.

Synthesis: Science and spirituality offer different but compatible and accordant understanding of the nature of reality.

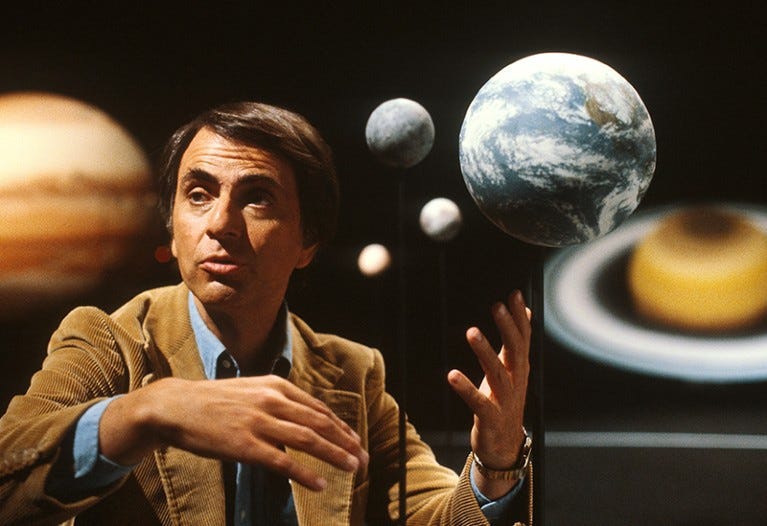

Carl Sagan to the Rescue

During my religious deconstruction process many moons ago, it was Carl Sagan who helped expel my evangelical fear of science. His book The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark impacted me deeply. Sagan wrote, “Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Deconstructionology with Jim Palmer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.