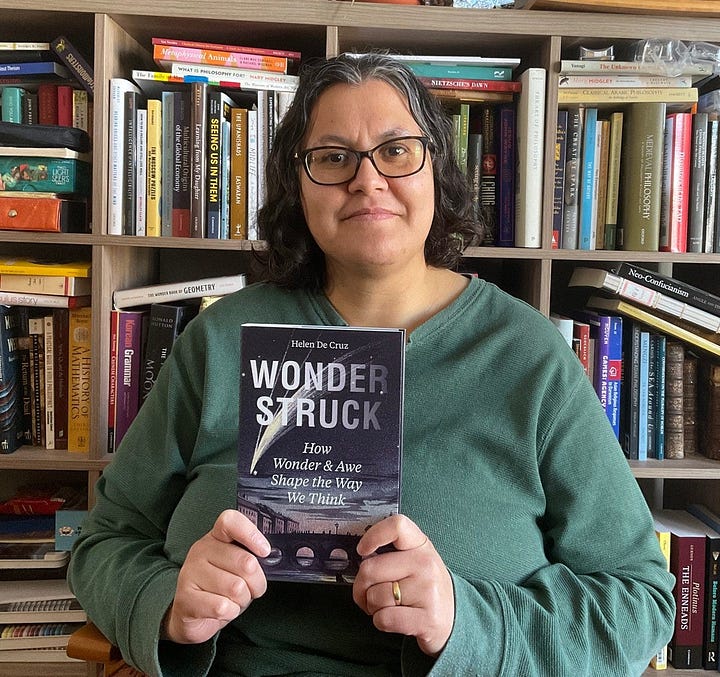

Among her many interests, which included philosophy, religion and art, Helen De Cruz loved mathematics. But yesterday, the only math equation that seemed to matter was 8,000,000,000 - 1. This week’s Week in Review is in remembrance of one we lost.

left this world Friday, June 20, 2025. She died at 47 after a long battle with Cancer. She is survived by her husband, Johan, and their children, Aliénor and Gabriel.

In her last published article she wrote:

“Seneca says that we have to die at some point. Our lives are a tiny flicker in a huge vastness of space-time. So does it matter when, exactly, we die? Or he says that when you know how to die, you’ve liberated yourself (from slavery). Moreover, I also think that I have been extremely fortunate to become as old as I am (mid-forties is historically old, many people did not survive their infancy), and I’ve been able to flourish as a human being in the full sense: with loving people around me, friends and family, doing things I enjoy doing, gaining professional fulfillment in writing and teaching. Many people never get to enjoy these goods (which is saddening). These are goods I enjoyed, no matter what the future holds.”

What jarred me personally about Helen’s death is that I knew her - had followed and studied her work particularly in the area of the philosophy of religion, and had connected and interacted with her on a number of occasions. The fact of her early death was also discomforting. She was only 47. Dutch philosopher, Baruch Spinoza, who she often wrote about, died at 44. Many of the world’s greatest minds never made it to 50 years of age. Though Seneca the Younger, who she quotes above, died at 68.

As a frame of reference, life expectancy in the era of Classical Greece was 25-28. The 1900 world average was 29-32, 1950 46-48, and in 2023 life expectancy was 73. The significant increase in global life expectancy after 1950 is primarily due to advancements in medical technology, particularly in the treatment of chronic diseases, coupled with improved access to healthcare, better sanitation, and healthier lifestyles. These factors led to a dramatic reduction in mortality rates, especially among children and young adults, and later, in middle-aged and older adults.

However, Cancer deaths continue to be concerning. In 2024, it’s estimated that there were 10 million cancer deaths worldwide. It’s estimated that there will be 620,000 cancer deaths in the US in 2025. Heart diseases is the most common cause of death, responsible for a third of all deaths globally. Cancers were in second, causing almost one-in-five deaths. Taken together, heart diseases and cancers are the cause of every second death.

Chances are you know someone right now or have lost a friend, colleague or loved one to Cancer. I share my own personal story of walking a person through the stages of dying from Cancer in my article, Human After All: A Brief Remembrance of The People You Don't See on Substack.

What touched me about Helen’s above words, some of the last she wrote, is her gratitude for the years she lived and how she lived them:

“I’ve been able to flourish as a human being in the full sense: with loving people around me, friends and family, doing things I enjoy doing, gaining professional fulfillment in writing and teaching.”

In her words, there’s a recipe of sorts for living life well:

Loving your neighbor

Stay close to friends and family

Doing more of what brings you joy

Offering your passions and gifts to the world

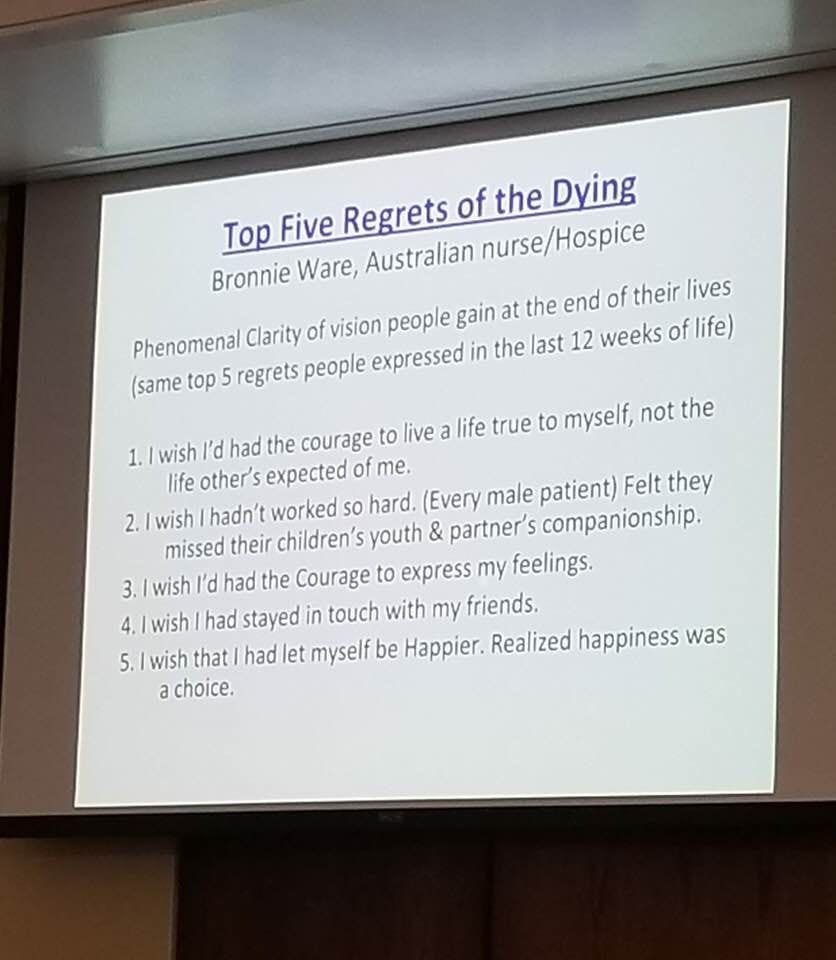

On BlueSky, Helen shared the below slide from Bronnie Ware’s book, The Top Five Regrets of the Dying: A Life Transformed by the Dearly Departing:

Born in Belgium, Helen De Cruz held the Danforth Chair in the Humanities at Saint Louis University. She obtained her PhD in philosophy at the University of Groningen in 2011, and a PhD in archaeology and art sciences at the Free University Brussels in 2007. Though having a broad range of interests, her main areas of specialization were philosophy of cognitive science and philosophy of religion. She also published work in philosophy of science, epistemology, aesthetics, and metaphilosophy.

A few of Professor De Cruz’s books, which I found especially meaningful are:

Religious Disagreement (Elements in the Philosophy of Religion)

A Natural History of Natural Theology: The Cognitive Science of Theology and Philosophy of Religion

An autobiographical interview with De Cruz can be found here. She was an Executive Editor of the Journal of Analytic Theology.

I was fortunate to have had a few conversations with Helen, which were instrumental in shaping my own thoughts in the philosophy of religion. One of her Substack articles that particularly impacted me was, DIY your own spirituality: On reading Spinoza's Ethics during a spiritual crisis. She influenced my own writing about Spinoza, perhaps most notably expressed in my article, Can You Be Atheist and Believe in God? Inside the mind of the world's greatest heretic.

Helen’s work is quite useful for anyone going through a process of religious de/reconstruction. I recommend watching her YouTube videocast below with Philip Goff, “Finding (and Losing) Their Religion”:

About her interests and work Helen wrote:

“Most of my published work attempts to understand why humans engage in philosophy, religious reflection, mathematics, art, and science. We spend what seem on the face of it outlandish amounts of time and energy on these pursuits, which appear to be inessential in keeping us alive in the struggle for survival and reproduction… Art, philosophy, and religion lay serious claims to being true human universals. If humans across times and cultures have found these pursuits worthwhile, we should ask why this is so. In my view, culture serves human needs and interests of us as biological organisms. They help us to expand our cognitive limitations and enhance our abilities.”

What particularly caught my attention was the paradox that existential reflection, such as philosophy and religion, are not essential for survival (food water, shelter) or reproduction, and yet they have endured as “human universals” to which are species has made a monumental investment. One way I will keep the memory and work of Helen De Cruz is by continuing to press into these questions through my work in the field of existential health.

In her last post on Substack Can’t Take it With You, Helen wrote:

“I am in hospice care and reflecting a lot on what a good life is. Writing is hard, this will take me days rather than just one morning or afternoon. But I want to share these thoughts. You can’t take it with you, yet we often feel ourselves immortal and act as if we can.

The richest man on earth is not happy yet he can buy and do whatever he wants. When we cherish people of the past they were not particularly wealthy. Marie Curie, Vincent Van Gogh, our wise grandmother … we love these people because of what they left us. Not because of what they had.”

What was it that Helen De Cruz left us? I can’t possibly measure the love, goodness, beauty and brilliance she brought into the world, or even into my own life. When I woke up yesterday morning it was 8 billion people minus 1… minus Helen De Cruz. The world is lacking in her absence, and will not be the same without her.

“Life is for the living.

Death is for the dead.

Let life be like music.

And death a note unsaid.”

- Langston Hughes, The Collected Poems

Inspired by all the resources you share.❤️🙏❤️

8 billion minus 1. And somehow the subtraction echoes louder than the sum.