The reference to the “recently departed” does not pertain to those who have recently died, but those who have left religion. I’ll refer to them as “Dones” - those who are done with religion.

This is an ode to the dones - a heartfelt address to those who walked away from the faith of their childhood and youth, or left a religion they felt betrayed or hurt them, or bid farewell to teachings and beliefs they could no longer accept.

Maybe you are one of them. There are many religion-leavers, and even more who don’t view religion favorably or necessary.

In the West, since at least the mid-twentieth century there has been a gradual decline in adherence to established Christianity. Typically referred to as the secularization of society, “non-religious spirituality” is gaining more prominence over organized religion. Institutionalized religion’s domination over culture has weakened, and more people make sense of their lives without traditional religious interpretations. The de-churching of America is a sign of the times.

Secularization in industrializing societies had been anticipated by many European thinkers in the 19th century, including the likes of Emile Durkheim and Max Weber, two of the founders of sociology. Weber spoke of the “disenchantment” of the world: the idea that increasing scientific knowledge would replace supernatural explanations.

Both Durkheim and Weber understood the reality of a “meaning crisis”, which has become a central cultural conversation today. I recently addressed this topic in the article, The Spiritual Emergency: Can we solve the meaning crisis before it's too late?

History repeats itself. The flight from religion and traditional societal mores is destabilizing. Just ask Fredrich Nietzsche and the can of worms he opened in 1882 when he declared “God is dead”. But God has nine lives at least, rising and declining in interest and devotion over the course of history and its cultural tides.

A substantial portion of adults worldwide are leaving the faith they were raised in. Younger adults and those with higher levels of education are more likely to leave their childhood religion. The trend is observed in various countries across Europe, the Americas, and East Asia. Christianity is experiencing significant losses in many countries, while the religiously unaffiliated are gaining members. Many individuals engage in a process of “deconstruction,” re-examining and questioning their religious beliefs.

Christianity, the largest religion in the United States, experienced a 20th-century high of 91% of the total population in 1976. This declined to 73.7% by 2016 and 64% in 2024. Pew Research Center projected that if the rate of decline continues to accelerate, Christians would make up less than half of the American population by 2070, with the estimated percentage for that year falling to 35%. Religious “Nones” (the religiously unaffiliated) are now the largest single group in the U.S. at 28% of the population, higher than Catholics at 23% and Evangelical Protestants at 24%.

The U.S. is experiencing the largest and fastest religious migration in its history. Over 40 million adults — including 15 million evangelicals — who used to attend a house of worship at least monthly have left church entirely.

There is a growing Exvangelical movement (2.5 million people), which is becoming more prominent on the American religious landscape. A recent poll indicated that more than 40% of self-identified evangelicals do not believe in the deity of Jesus, a longstanding central tenet of evangelicalism. The Ex-Mormon movement has also exponentially grown in recent years. Statistics indicate that 40% of those born into the Mormon faith leave, with a large portion (58% of those who leave) becoming unaffiliated with any religion.

Generation Z (born between 1999 and 2015) is the nation’s least religious generation. It’s not only a lack of religious affiliation that distinguishes Generation Z. They are far more likely to identify as atheist or agnostic. The percentage of Gen Z that identifies as atheist is double that of the general U.S. population. It appears Generation Alpha will be following in their steps, unlikely to identify with traditional religious institutions and practices, and exploring spirituality online, seeking information and community through digital platforms.

If you want to explore the topic of the secularization of society further, you might find this book useful: Beyond Doubt: The Secularization of Society by Kasselstrand, Zuckerman and Cragun.

Done With Religion

My departure from religion was a public and scandalous controversy. The scandal was how a theologically-trained megachurch pastor who had devoted his life to teaching the Bible and advancing the Christian religion could suddenly just walk away, renounce it all, never to be heard from again. Of course, that’s not the way it really was. For a string of years, I had increasingly grown deeply conflicted about my Christian theology and lived in denial of the harm it was doing. I tell the story in my published article, Confessions of an Ex-Megapastor.

There are many reasons why a person leaves religion. People are becoming more ideologically progressive, while their religious organizations are stagnant and anachronistic.

People often report intellectual reasons for leaving religion, or say they simply outgrew their faith. The highly educated are more prone to leave religion. This is not only people with higher levels of formal education, but also self-learners with more accessible online options to seek new knowledge. Many of the beliefs of traditional religion defy rational thinking and deny modern science.

A person might walk away from religion because they cannot endorse the values of their previous religious organization, including their views on LGBTQ+ individuals, stances on gender or sexuality, or pervasive sexism and racism. Many major Christian denominations are embroiled in debate and division over these issues, and this often becomes the reason for one’s departure from religion.

Other people leave because of religious or spiritual trauma or abuse. They have experienced this abuse firsthand themselves, or know people who have. A recent study indicates that 1 in 3 Americans suffer religious trauma, which occurs when a person’s religious experience are emotionally, psychologically or spirituality harmful or abusive. A significant element of my professional work has involved counseling people who were harmed by toxic religion.

Religious Trauma Syndrome is a term used to describe the symptoms and effects of harmful religious experiences. These experiences often stem from high-control or authoritarian religious groups, spiritual abuse, or dogmatic teachings that instill fear, shame, or guilt. It is expected that Religious Trauma Syndrome will be included in the 6th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

Religious trauma does not exclusively pertain to obvious examples such as extreme cults. Controlling, authoritarian, or abusive religious environments can appear contemporary, friendly and family oriented on the surface. Harmful religion is not just a David Koresh compound in Waco, Texas, but can be the Baptist or Evangelical church on the corner in Niceville, Florida.

There are also those who leave organized religion because of abuses perpetrated at an institutional level (for example, by Catholic priests). For many, walking away is an act of courage and protest.

Some leave their faith because of suffering. Many have been given theologically thin accounts for the existence of evil in the world. People often struggle to make sense of what they were taught in light of their own life experiences. How does one square the belief in an omnipotent, omniscient and omnibenevolent God, with a world of oppression, injustice and brutality. I discuss this dilemma in my article, Why won't God stop evil and suffering?

There are those who no longer identify as religious because they find labels problematic. Take the term, “Christian”. Are we talking about a far-right, fundamentalist Christian Nationalist “Christian”, or a progressive, social justice, DEI “Christian”? There is too much baggage associated with most religious labels, and increasingly people do not want to be shrink-wrapped into a fixed religious belief-system or ideology, or associated with a contemptible stereotype.

There are many reasons why a person might feel conflicted about their religious beliefs and affiliation. The trigger can be episodic such as personal tragedy, major life changes, church scandal, hypocrisy, or an experience that challenges their beliefs. In other instances, a person’s faith gradually erodes as they question the credibility of religious teachings in light of new information, opposing views, and exposure to different spiritual perspectives, philosophies, worldviews and areas of knowledge.

These are some of the different dynamics that relate to why people leave religion. Every scenario is different and there is an intersectionality dimension that recognizes that how people are harmed by religion and the hardships of separating from one’s faith, are influenced by factors such as one’s gender, race, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

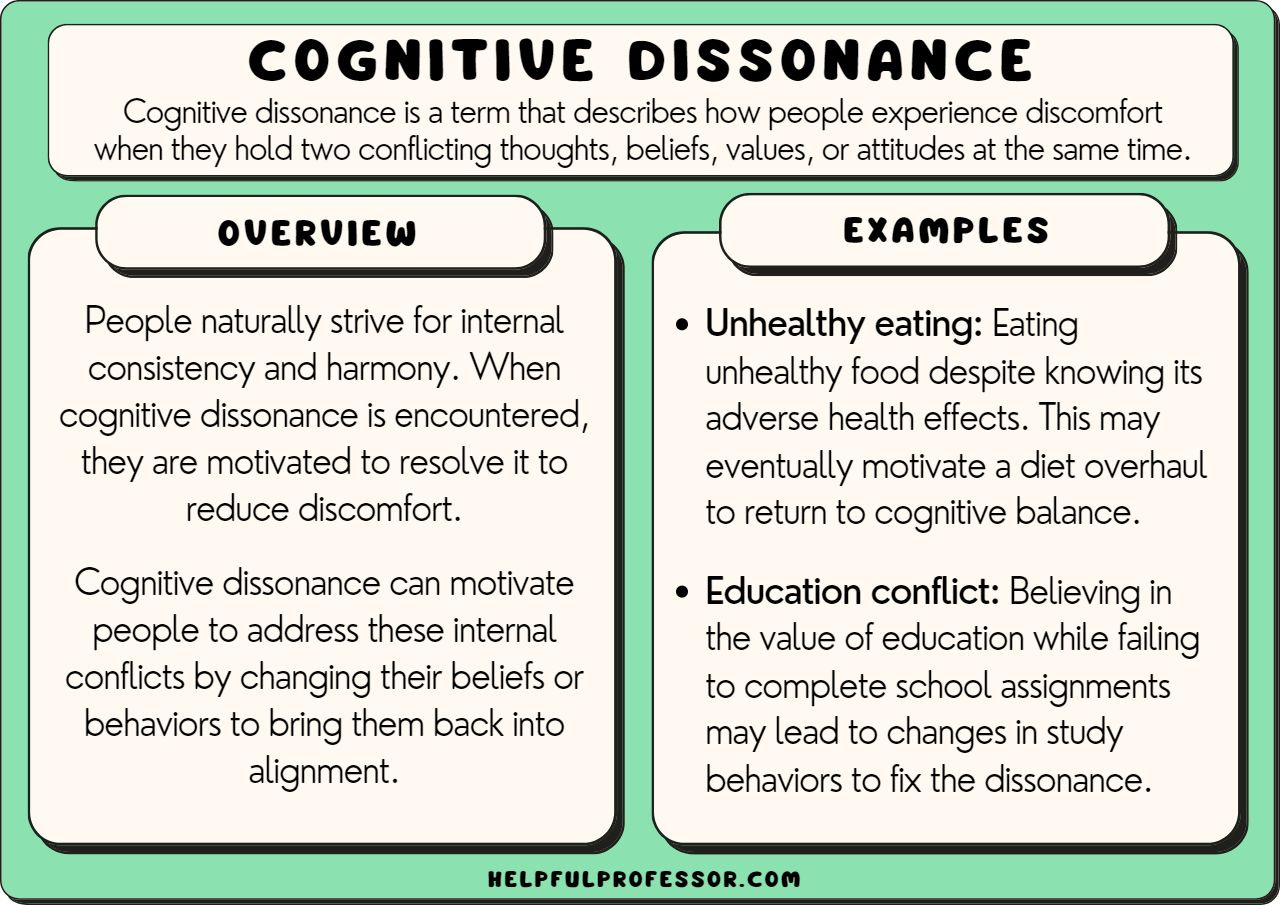

There does, however, seem to be a common underlying feature in why people leave religion: cognitive dissonance.

Most people have a general understanding of what cognitive dissonance is. In my view it’s worth exploring the theory more deeply, which you can do by reading A Theory Of Cognitive Dissonance by Leon Festinger.

Cognitive dissonance theory posits that individuals seek to maintain consistency among multiple cognitions (e.g., thoughts, behaviors, attitudes, values, or beliefs). Inconsistent or antithetical cognitions produce inner distress that motivates individuals to change one or more cognitions to achieve consonance.

In psychology, consonance refers to a state of harmony and alignment between one’s beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and actions. People often feel they are living fragmented and discordant lives, and seek a more integrated, whole and unitive lived human experience. When one’s words and actions are aligned with their core internal beliefs and values, consonance is realized. When there’s consonance, you feel a sense of well-being, satisfaction, and psychological comfort.

For many people, leaving religion and changing their beliefs is an effort to alleviate cognitive dissonance, and achieve consonance.

Here are a few examples of cognitive dissonance related to religion:

You attend a church that teaches creationism and yet you are convinced that evolutionary biology best explains the origins of the universe.

You have found deep wisdom in other religious traditions and spiritual paths, but your religion claims its teachings are the only and absolute truth.

A family member or close friend comes out as gay, but the stance of your church is that homosexuality is a sin and condemned by God.

A woman shares her history of abuse and domestic violence, and one of the responses is, “God won’t give you more than you can handle.”

Your church pastor is winsome, charismatic, and loved by all, but you’ve witnessed multiple instances when he was arrogant and sexist.

You struggle with anxiety or depression, but you’ve been told that trusting God, prayer, and Bible study are all you need to be well.

You find meaning in the teachings and life of Jesus, but you feel that your Christian church mostly misses the point of what Jesus was about.

One of the regular worship songs you sing in church is titled, “God is Good All the Time”, but you can’t square this with the recent elementary school shooting in the news headlines.

You attend church twice a week, faithfully tithe and actively involved, but despite your busy religious life, you feel disconnected, adrift and a deep spiritual emptiness.

One’s religious commitment might prevail with some measure of cognitive dissonance. Afterall, there’s a lot to lose with the decision to leave one’s religion, including the loss of relationships, community and one’s entire social network. In many instances, leaving one’s religion can involve rejection, shunning and harassment.

Some people opt for a cultural Christianity, identifying with Christian values, traditions, and cultural aspects of Christianity without necessarily adhering to its core theological doctrines or actively practicing the faith. Flannery O’Connor wrote, “She was a good Christian woman with a large respect for religion, though she did not, of course, believe any of it was true.”

But for many others the cognitive dissonance becomes vexing and intolerable. The cost of staying becomes greater than the cost of walking away.

Leon Festinger also published a book titled, When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of A Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World. The book is based upon a study he and others did on a small UFO religion in Chicago called the Seekers that believed in an imminent apocalypse. Festinger wrote:

“When people are committed to a belief and a course of action, clear disconfirming evidence may simply result in deepened conviction and increased proselyting. But there does seem to be a point at which the disconfirming evidence has mounted sufficiently to cause the belief to be rejected.”

After You Leave

No two leaving-religion journeys are the same, but I’ve observed a few places where people seem to land. I identify them as:

Early Questioners

Newly Single

Stuck Leavers

Angry Camp Dwellers

Nihilistic Nomads

Wide-Eyed Explorers

Let me briefly describe them.

The Early Questioner

The Early Questioner is someone sitting in a church service somewhere and fighting off feelings of cognitive dissonance, stemming from the irreconcilability of their religious beliefs with rational thinking, new knowledge or real world realities. At first, this person is likely to rationalize continuing their religious involvement, repressing their doubts, and focusing on the positive. But once the questioning begins, it often intensifies and becomes intolerable.

This is a difficult place to be in light of what the questioner will likely lose if they listen to their doubts and walk away. Because so much is wrapped up in a person’s involvement in religion, leaving could mean a loss of identity, relationships, and the unraveling of their core beliefs about God, and the meaning and purpose of life. I received a flood of emails from early questioners after my first book, Divine Nobodies: Shedding Religion to Find God (and the unlikely people who help you).

Do I stay or should I go? This is a difficult question for the Early Questioner. It requires a person to honestly evaluate whether their religious involvement fosters or diminishes their psychological, emotional and spiritual health. It could be worthwhile to ponder this question in light of tools such as the Adverse Religious Experiences Questionnaire or this spiritual abuse self-assessment.

Newly Single

There are some who would liken the process of leaving religion to going through a divorce. In this case, divorcing religion. A person might stay in a relationship (or religious belief) longer than they should because they’ve invested so much time and effort into it. But at some point the cost of staying outweighs the cost of leaving. The “newly single” person in the leaving-religion process is the person who just left. They walked away. It’s final. They’re not going back. Using divorce as a metaphor for leaving religion highlights the emotional weight and disruption that often accompanies such a decision.

The challenges of leaving religion are daunting. For most people, the religious environment was a one-stop-shop for meeting all their major needs – social support, a coherent worldview, meaning and direction in life, structured activities, and emotional and spiritual satisfaction. The “newly single” religion-leaver often experiences a spectrum of volatile emotions including grief, doubts, confusion, anger, sadness, fear and denial. In many cases, one’s core beliefs and assumptions are shattered.

Leaving religion often involves an identity crisis, adjusting to an unfamiliar way of life, inner turmoil, and the loss of friends and family. It is typically a lonely, destabilizing and stressful life event. For some people it may be possible to simply stop participating in religious services and activities and move on with life. But for others, leaving their religion can mean debilitating anxiety and depression. Making the break is for many the most disruptive, difficult upheaval they have ever gone through in life.

Ending one’s relationship with religion can be a positive and empowering experience, leading to personal growth, self-discovery, and a renewed sense of freedom. It can be a liberating opportunity for a fresh start and a chance to build a more fulfilling life. But for many people, the mental health harms and human development deficits left behind by toxic religion can make rebuilding difficult.

I’ve published several articles related to the newly-single religion leaver including:

Stuck Leavers

The Stuck Leaver is the person who for all intents and purposes has left religion. They quit attending church, discarded many of their former beliefs, and have unplugged from religious sub-culture.

You can take a person out of religion, but it’s much more difficult to take religion out of the person. The harmful effects of toxic religion are deeply rooted, and will continue sabotaging a person’s life long after they leave church. You can walk away from organized religion - its structures, practices, doctrines and functions - but continue to suffer the mental health consequences and human development deficits left behind.

There is personal work that must be done to truly liberate oneself from toxic religion. It could include trauma work, addressing religious pathology, and the healing, recovery and repair of one’s relationship with themself.

There are two essential components of the leaving-religion process: “deconstruction” and “reconstruction”. The deconstructive aspect involves the critical examination of one’s inherited, learned or indoctrinated belief-system, and the renunciation of those beliefs, mindsets, narratives, doctrines, practices and behaviors that one can no longer accept in good conscience. Walt Whitman wrote, “Re-examine all you have been told in school or church or in any book. Dismiss whatever insults your own soul; and your very flesh shall be a great poem.”

The reconstructive side to the leaving-religion process is cultivating new mindsets and learning new tools for living life meaningfully. Deconstruction addresses the cognitive dissonance, reconstruction builds consonance.

My second book, Wide Open Spaces, continues my leaving-religion story as I began stumbling my way forward, trying to figure out my life after the collapse of my religious identity, belief in God and ministerial career. Each chapter revolves around a question I had to wrestle through as I disentangled myself from my religious conditioning.

After being contacted by so many early questioners after my first book, I felt a responsibility to share what my first steps into my post-religion life looked like. It wasn’t always pretty, but it was real. I recently published an article about what life initially looked like for me after leaving religion, 10 Things I Stopped Doing After Leaving Religion.

I encourage stuck leavers to create an exploration and rebuilding space in their lives. It doesn’t have to be a monumental time and energy commitment. Maybe it’s 15 minutes a day, an hour once a week, or a couple hours on the weekend.

I sometimes use questions like these with people who feel stuck. You may find a few of them useful.

What makes you come alive?

When does life especially feel meaningful to you?

What brings you joy?

What centers you?

What new areas of knowledge or experience are you most curious about?

What makes you feel connected to yourself?

What forms of self-expression are the most gratifying?

What way of being in the world resonates most deeply with your heart?

If you enrolled in a free online class, what would it be?

How are you most compelled to convert a personal conviction in a deeper engagement with the world?

If you made a new commitment to practicing self-care, what would it be?

What interest, passion, curiosity, adventure or hobby would motivate or inspire you to connect with others or a group?

The answers to these questions may be useful for creating a new space in your life to explore and get unstuck.

I also have one small assignment for stuck leavers, which is to read my recent article, More Human.

One last suggestion for stuck leavers is to consider the idea of taking initiative to cultivate a more vigorous intellectual life.

Angry Camp Dwellers

There are many good reasons for a person to be in opposition to religion. It’s abundantly clear that toxic religion is often a weapon of hate, destruction, injustice, corruption and violence in the world. It’s not necessary to substantiate this claim because it is self-evident from a cursory examination of history and daily news headlines.

It’s a normal response for a person to detest that which caused great harm to them or those they love. If someone has been traumatized by religion or seen its deleterious effects in the lives of others, it’s unlikely they’ll go quietly into the night. Any person who feels betrayed or victimized by their religion will likely become it’s biggest critic, and opposition their greatest cause.

Confronting toxic religion is necessary in the interest of advancing and safeguarding individual, collective, societal and planetary flourishing. I am grateful for those throughout history who vehemently and publicly condemned the toxicities and absurdities of harmful religion. Friedrich Nietzsche, Bertrand Russell, Simone de Beauvoir, Richard Dawkins, and Christopher Hitchens are a few who come to mind.

However, what sometimes happens is that a religion-leaver becomes mired in a never-ending crusade against religion, which often devolves into highly charged social media debates, and an onslaught of inflammatory anti-religion memes.

I'm not saying we should not confront the toxicity of religion. However, consider the possibility that we must go further than this and live the alternative. It’s always easier to plant your flag on what you are against, but what about living your way into what you are for?

A person must consider the toll of waking up each day to rail against the absurdities of religion. That’s why you left. Right? Because it was absurd. Why rehash this every day? What is this doing for you? I'm not saying to stop exposing and opposing the damage that toxic religion does. I’m saying don’t make it your main or only thing. It’s common for religion-leavers to simply switch sides from being a follower of religion to an adversary of religion. You can become a fundamentalist either way. Notice that in both cases, the reference point is still religion. Consider the possibility of creating a new direction for your life that doesn’t revolve around religion, either for it or against it.

If you have been psychologically, emotionally or spiritually harmed through your involvement in toxic religion, seek the help, resources and support you need. This is one of the central reasons why I founded the Center for Non-Religious Spirituality. This Substack newsletter also offers useful resources. A few of the perks in appreciation of those who support the cause at $5 monthly or $50 annually, receive the following free digital books:

Life After Religion: A 30-Day Detox Guide

How to Have a Great Day Without Religion: A Universal Handbook for Living Life Well

The Deconstructionology Encyclopedia (Volume One)

If you are not in a place where you can afford the $5, let me know and I’ll comp you a “paid” membership to make these available to you. I also created the The Leaving-Religion Resource Guide, which is an extensive list of resources pertaining to the religious deconstruction process, and healing and recovery from religious trauma.

Many atheists believe that religion in any form does more harm than good, and is an obstacle to progress. To the extent that a person believes that all religion is fundamentally flawed, threatens progress and poisons everything, they will not roll over and play dead in a society where religion has great influence in every segment of life - culture, education, government, politics, social media, etc. As a matter of conviction, many atheists feel they must counter and criticize religion. I get it.

On the other hand, in my opinion, Atheists could be more useful to religion-leavers by doing more than opposing and vilifying religion. I recently discussed this in a couple articles:

It’s also worth noting that in the United States, freedom of religion is a constitutionally protected right provided in the religion clauses of the First Amendment. Freedom of religion is also closely associated with separation of church and state. People are free to hold, express and practice religious beliefs, and people are free to hold, express and practice secular beliefs. In the United States, you have the legal right to believe and practice Christianity, Atheism, Judaism, Humanism, Islam, Stoicism, Buddhism, Hinduism, etc… It’s a good idea that we all remember this.

Any belief-system, philosophy or ism can become fundamentalist. You can be a Christian fundamentalist, Buddhist fundamentalist or Atheist fundamentalist. A fundamentalist atheist insists that their way of seeing the world is the only legitimate way, and anything else is ignorance, stupidity or mental illness. To some atheists, not subscribing to their views makes you the infidel.

Atheists also need to realize that not all religious people are fundamentalists. An atheist’s particular view or experience of religion is not representative of every person’s idea and experience of religion. Though religion has often been the source of hatred, division, corruption, injustice, brutality and violence in the world; it has also inspired compassion, beauty, justice, service and love in the world.

Nihilistic Nomads

I often use the phrase “deconstruct to reconstruct”. In other words, questioning, critically examining, dismantling and discarding one’s former religious dogma, clears the ground to freely reconstruct new and different mindsets, beliefs, values and ways of being in the world that a person finds most meaningful and liberating. I spoke of this previously as a shift from cognitive dissonance to psychological or existential consonance.

In some cases, however, a person can deconstruct… and deconstruct… and deconstruct… and deconstruct… down to the studs of human existence. And without any reconstruction, a person can deconstruct down into a black hole of nihilism and existential despair.

In my opinion, religion often sets people up for this dilemma. Religion wraps the totality of one’s identity and existential grounding around the master-signifier of “God”. There’s an existential co-dependency dynamic that occurs. Essentially, nothing of worth or value can exist apart from relationship with “God”. No grounded identity, no meaning or purpose to life, no security or certainty, no existential architecture, no absolute truth or basis for morality, no answer to human suffering or human mortality, no true love or belonging, no blueprint for how to live, no chance for well-being and happiness… apart from relationship with “God”.

Meanwhile, religion often simultaneously prevents a person from cultivating the skills and tools to address these matters outside the “God”-framework. I often refer to these as “human development deficits”, which includes a significant lack of knowledge related to healthy human development, as well as delayed emotional maturation and poor critical thinking ability.

You can see the problem, right? A person’s entire existential grounding is anchored in co-dependency with “God”, their deconstruction process detonates the theological scaffolding on which “God” is predicated, and they are left dazed and stumbling through the religious rubble without the tools, skills or developmental capacities to survive. It doesn’t necessarily take a lot to end up there. Spend an evening reading the existential philosophers, and a recent religion-leaver might very well be on the verge of an existential breakdown.

I have addressed this subject previously in articles such as:

In my psychology of religion series I published an article on how nihilism can be good, and even a healthy and necessary part of one’s spiritual journey. Of course the question of “God” often comes up, which I have written extensively about in articles such as:

It’s not necessary for a person to wander around aimlessly in the clutches of existential nihilism. I joked about existential philosophers, but their thoughts on approaching the deep questions of life outside the religious framework can be quite helpful. A couple articles I published on existential philosophy include:

Identifying “nihilistic nomads” is an acknowledgement that many people in our times struggle with nihilism and existential dread. A central part of my professional work is to promote and foster what I call “existential health”, which is being in constructive relationship with the givens of human existence (human mortality, human groundlessness, human insatiability, and human isolation). A few articles I have written on this include:

Tick-Tock, Tick-Tock: Afraid to die and the search for the immortality formula

The Great Reconstruction (six-part series)

In 2021 I created a training and certification course for Non-Religious Spiritual Directors and EXiHealth Practitioners who are specifically trained to address the fallout of our current meaning crisis, and work with people struggle with nihilism and existential anxiety, and in need of reconstructive guidance and support. I discuss these dynamics in more detail in the article, The Spiritual Emergency: Can we solve the meaning crisis before it's too late?

Wide-Eyed Explorers

My most recent Week in Review was titled Be the Explorer, in which I discuss the Jungian archetype of the “explorer”. In that article I also identify several people on Substack to read and follow in order to learn new things. I do the same in the piece, Week in Review: The 20 People You May Not Know... Edition. I hope you will take the time to explore all these suggestions in the interest of exploration. is someone I recommend you follow and his Substack newsletter devoted to self-learning and autodidacticism.

It’s not an easy thing for most religion-leavers to become wide-eyed explorers. This is because toxic religion is built upon fear, which includes:

Fear of having wrong beliefs

Fear of trusting yourself

Fear of thinking for yourself

Fear of questioning authority

Fear of other fields of knowledge

Fear of people with different beliefs

Humanist and freethinker, Robert G. Ingersoll, expressed the conversion of a religion-leaver to a wide-eyed explorer with these words:

“When I became convinced that the universe is natural – that all the ghosts and gods are myths, there entered into my brain, into my soul, into every drop of my blood, the sense, the feeling, the joy of freedom. The walls of my prison crumbled and fell, the dungeon was flooded with light and all the bolts, and bars, and manacles became dust. I was no longer a servant, a serf or a slave. There was for me no master in all the wide world - not even in infinite space. I was free - free to think, to express my thoughts; free to live to my highest truth; free to live for myself and those I loved; free to use all my faculties, all my senses; free to spread imagination’s wings; free to investigate, to guess and dream and hope; free to judge and determine for myself; free to reject all ignorant and cruel creeds, all the “inspired” books that ancients have produced, and all the bygone legends of the past; free from popes and priests; free from all the “called” and “set apart”; free from sanctified mistakes and holy lies; free from the fear of eternal pain; free from the winged monsters of the night; free from devils, ghosts and gods. For the first time I was free. There were no prohibited places in all the realms of thought - no air, no space, where fancy could not spread her painted wings; no chains for my limbs; no lashes for my back; no fires for my flesh; no master's frown or threat; no following another's steps; no need to bow, or cringe, or crawl, or utter lying words. I was free. I stood erect and fearlessly, joyously, faced all worlds.”

“Wide-eyed” describes someone experiencing wonder or astonishment, often with their eyes fully open, while “explorer” refers to someone who travels to new and unfamiliar places, seeking knowledge or adventure. A wide-eyed explorer is someone who approaches new discoveries with a sense of awe and curiosity.

German mystic, Meister Eckhart, wrote, “Be willing to be a beginner every single morning.” You’ve likely heard of the “beginners mind” or the Zen concept of “shoshin,” from Zen Buddhism. Shunryu Suzuki’s book Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind is a classic work on the subject. Suzuki wrote, “In the beginner's mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert's mind there are few.”

My hope is that all religion-leavers will feel the freedom to be wide-eyed exploeres.

To “Dones” with Love

Writing love letters to people done with religion wasn’t my idea. It was recommended that I write them as a way of thinking through the different places people find themselves after losing faith and leaving religion. I decided to include one love letter in this article to the Newly Single.

Dear Newly Single,

You can do hard things. You’re proven that. You walked away from a toxic and abusive relationship with religion.

I want to acknowledge you. It takes courage to walk away. Breaking free from a toxic religious background is one of the most difficult things a person will ever do. Becoming a whole, integrated and authentic human being almost always involves questioning inherited beliefs, pushing through the pressures of conformity, and thinking for yourself. Most people will not do these things, but this you have done. Congratulations!

Leaving religion is not for the faint of heart, requiring bravery and fortitude. No one can fully understand or appreciate the journey you have walked. I’m not going to pretend to understand what religion took from you, the harm it did, and what it cost you to leave.

Maybe you feel overwhelmed. It’s understandable.

Leaving religion is emotionally taxing. I experienced feelings of loss, anxiety, guilt, anger, confusion, and fear. I’m guessing you’ve had to deal with strained relationships with family and friends, and loneliness.

For me, leaving religion was a loss of identity. My religious belief-system was the foundation of my worldview, values, and sense of meaning and purpose in life. It supplied the answers to the big questions about God, the afterlife, and ultimate truth. Leaving left a void, a list of huge unanswered questions, few absolutes to lean on, and a lot of existential angst. Separating from religion also brought practical challenges like reshaping my social world, navigating career and financial changes, and facing judgement, rejection and harassment.

In a nutshell, leaving religion can feel like starting over… from scratch… in the rubble of your former religious life… with little support… and no idea how or where to begin. You left. Now what? A “fresh start” can be paralyzing. I can relate.

It’s scary, isn’t it - to have doubts, question your lifelong beliefs, and frightfully wondering where all this ultimately leads. I get it. If you’re feeling a maelstrom of inner confusion and conflict, I understand. Consider the possibility that life is an evolutionary process of becoming. As a human being, you were born with an inbuilt proclivity toward growth and the actualization of your fullest potentialities and possibilities.

Change is often painful. Anais Nin wrote, “And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom.” Maybe this is that day for you - a risky but blossoming season. It naturally feels risky because you are questioning what you’ve always known, losing sight of the shores of familiarity, and feeling the fear of the unknown. It’s unnerving to let go of the answers and explanations you’ve held for so long without something to replace them or solid to hold onto.

Wendell Berry wrote, “It may be that when we no longer know what to do, we have come to our real work, and when we no longer know which way to go, we have begun our real journey.” The space of not knowing can be discomforting. The “real work” of this blossoming season might be navigating this uncertainty. Be patient with and have compassion on yourself.

In Letters to a Your Poet, Rainer Maria Rilke wrote:

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.”

The salient point here is to consider the possibility that finding answers is not the endgame, but rather to learn to be with and live the questions. To shift this from the poetic to the practical, perhaps cultivate a mindset of curiosity, wonder and introspection. See your questions not as problems to be solved, but as doorways to new possibilities and deeper understanding.

I remember being where you’re at now, thirty years ago. I still don’t have all the answers and I continue to live the questions, but I have found this to be a path of growth and liberation. Living things are constantly evolving. The only time you don’t change is if you’re dead. The gift of life is its never-ending invitation of becoming. You are not alone. There are countless people who are where you’re at, with all the volatile feelings you may have. There are people and places where you can find acceptance, validation, understanding and support. There are people who care and will walk this journey with you. One of them is me.

Jim

In Summary

For all kinds of different reasons, people are done with religion, and there are lots of them.

Religion often causes a cognitive dissonance that becomes vexing and intolerable, and the cost of staying becomes greater than the cost of leaving.

There are two essential components of the leaving-religion process: “deconstruction” and “reconstruction”.

Reading existential philosophy might put you on the verge of a nihilistic meltdown, but it can also become a path of deep freedom.

It’s always easier to plant your flag on what you are against, but what about living your way into what you are for?

I hope every religion-leaver becomes a wide-eyed explorer.

Thank you for reading this article. I realize it was wrong. Thank you for subscribing to my Substack 🙏🏼🤗☕

“The secret of happiness is freedom. The secret of freedom is courage.”

- Thucydides

Deeply worthwhile. Thank you.

Please check for autocorrected words that change your meaning. Near the end you mean ‘long’ I believe, but the word there is “wrong”…

Thanks for that. It does a really nice job of helping sort out some phenomena that are often difficult to not mix together in confusion.

As an American Unitarian Universalist (with various ventures into other religion along the way), I could not help but notice that many (not all) of the motives and categories said to me "that person should explore UUism". More of our members are refugees from Christianity, from of one of the categories you identify, than were raised UU.

It is interesting that most who came to UUism from Christianity decidedly reject Christianity now, whereas those with different religious histories (not many, but there are some) tend to incorporate those into their UUsim. I recently gave a sermon on reading the Bible as a UU -- how to possibly appreciate it even while rejecting the Christian church(es) -- and a lot of the reaction was utter surprise, far more than it might be for how to read the Bhagavad Gita as a UU, even though the latter is much further from most of what we do/think/believe.

It makes me wonder how much of the "none"-ism that you talk about is specific to American/Western culture and Christianity. The acculturation leads people to feel that Christian-influenced beliefs have to be either all-in or all-out, with no room for nuance and partial rejection as there might be for other faith traditions.