God in Mind: The Psychology of Religion

Part Three: Does Religion Unlock or Shut Down Our Transcendence?

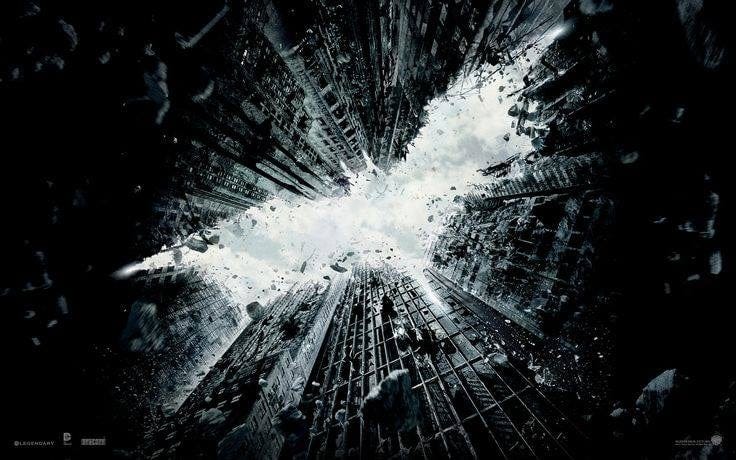

In Batman Begins Bruce Wayne says:

“People need dramatic examples to shake them out of apathy, and I can't do that as Bruce Wayne. As a man, I’m flesh and blood. I can be ignored. I can be destroyed. But as a symbol, as a symbol I can be incorruptible, I can be everlasting.”

Carl Jung was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology. Jung believed in the power of symbols for human development and self-actualization. He believed transformation is not possible without a symbol. Jung saw religious symbols as expressions of deep psychological truths. He wrote:

“There are, and always have been, those who cannot help but see that the world and its experiences are in the nature of a symbol, and that it really reflects something that lies hidden in the subject himself, in his own transubjective reality.”

Maybe we all are a Bruce or Brenda Wayne, just one symbol away from a sublime self.

This is the third installment of my series, “God in Mind: The Psychology of Religion”. My exploration of psychology was instrumental in my own religious deconstruction and reconstruction process. Many people leave religion with human development deficits, such as a lack of knowledge in critical areas of individual growth. Psychology is one of those unknown fields for many religion-leavers. Sadly, traditional religion often casts a shadow of suspicion and contempt upon secular psychology and the professional mental health field.

An article such as this requires a commitment on your part. Think of all my articles as a resource that you can always come back to as you do your own personal work. I don’t want to tell you how to read this article but here are a few thoughts I hope you find useful:

Feel free to read this article in parts. As a “paid subscriber” you will always have access to this (and all) my articles.

Use the article for ideas to apply in your process of post-religion reconstruction or for cultivating a more authentic, meaningful, liberating and profound spirituality.

Choose one or two of the recommended resources to explore Jungian psychology further in light of your own journey.

Just to clarify at the outset, here’s what I am NOT doing in this series. I am not discussing the psychology of religion in order to question, undermine, debunk and dismiss all religious faith and experience. What I hope to achieve in this series includes:

Introduce people to the field of the psychology of religion to aid their process in cultivating a meaningful and liberating non-religious spirituality.

Point out ways that the insights from the psychology of religion can aid people in a faith transition, existential crisis, religious deconstruction process, or addressing the dynamics of Religious Trauma Syndrome.

Demonstrate how to utilize the field of the psychology of religion to develop critical, nuanced, balanced, compassionate thinking about the phenomenon of religion.

The previous first two installments of this series are:

Part One: Its All in Your Head (Or Is It?) → Series Introduction

Part Two: Is Religion Illusion, Delusion or Prehension? → Sigmund Freud and Religion

In today’s article I’m going to be covering aspects of Carl Jung’s psychological insights into religion.

Here’s my typical disclaimer: Not only can I not scratch the surface on Jung’s contribution to the field of psychology, I can’t even scratch the surface on Jung’s psychological insights into religion. I will briefly cover a few of these insights, and recommend additional resources to explore further if you are interested.

I’m inviting you to think of this article, not in terms of “religious deconstruction” (the critical examination and unlearning or toxic religious mindsets and teachings), but with respect to “religious reconstruction” (cultivating a meaningful, authentic, liberating post-religion spirituality). My hope is that you will identify some aspect of Jungian psychology to aid your human development and spiritual growth journey.

Who is Carl Jung?

Many years ago I was trained in Jungian psychology as a certified spiritual director (CSD), and I include a section on Carl Jung in my training and certification course for non-religious spiritual directors. These men and women are specifically equipped to work with people in areas such as: faith transition, existential crisis, deconstruction and reconstruction, religious trauma, non-religious spirituality and existential health.

One of Jung’s central ideas was that the purpose or meaning of life was what he called “individuation”, which is the actualization of one’s fullest and unique possibilities and potentialities. He wrote: “The privilege of a lifetime is to become who you truly are.” To achieve this, Jung believed it was necessary for a person to integrate both the conscious and unconscious parts of who they are.

This is an important insight to consider. Is true transformation simply a matter of our conscious beliefs and changing our behavior, or do other dimensions of the psyche need brought into the process?

Mahatma Gandhi wrote, “I like your Christ, I do not like your Christians. Your Christians are so unlike your Christ.” What accounts for the disparity between the example of the life of Jesus and the lives of many Christians? The tagline of modern Christianity is WWJD?, and the implication is that a true Christian should imitate or behave like Jesus. So why does this seem so hard to do? Religion has a clever way of giving people an out by saying Jesus is God and you are not.

But is there another reason that makes each if us accountable for who we are? Could it be that Christianity fails to understand all the relevant dynamics involved in becoming a whole human being? Correct theology, memorizing Bible verses, prayer and regular church attendance may make you a “good Christian” but fail miserably at making you a profound person.

Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) was one of the leading pioneers of modern psychology and widely regarded as one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century. Born in Switzerland, he first became a physician and then entered the emerging field of psychoanalytic psychiatry. Albert Bandura said that Jung was a “master physician of the soul” and “one of man’s great liberators.”

Carl Jung’s religious upbringing was influenced by his father, a Christian pastor of a rural Swiss church. It is said that his father was often irritable. I get it. I was a pastor myself, which provided plenty of reasons for an ill temperament. It was hoped that Carl would follow in his father’s ministerial footsteps, but it wasn’t to be as his continuing interest in psychology caused Carl to call into question the claims of orthodox Christianity.

Jung’s beliefs about God and religion are not clear-cut. He is generally not considered to have been a Christian, but he did use his Christian background to explore the psychological roots of religion. Carl Jung believed that religion was a symbolic expression of life’s meaning and a psychological response to the unknown.

Jung wrote:

“It is the role of religious symbols to give a meaning to the life of man. The Pueblo Indians believe that they are the sons of Father Sun, and this belief endows their life with a perspective (and a goal) that goes far beyond their limited existence. It gives them ample space for the unfolding of personality and permits them a full life as complete persons. Their plight is infinitely more satisfactory than that of a man in our own civilization who knows that he is (and will remain) nothing more than an underdog with no inner meaning to his life.”

Over the door at his house in Zurich, Jung had inscribed: “Whether summoned or not, God will be present.” This sums up Jung’s attitude on religion and spirituality, in his life and in his work. “God” is not an objective external reality but a deep psychological phenomenon. Jung wrote:

“If I accept the fact that a god is absolute and beyond all human experiences, he leaves me cold. I do not affect him, nor does he affect me. But if I know that a god is a powerful impulse in my soul, at once I must concern myself with him, for then he can become important.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Deconstructionology with Jim Palmer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.