“Christianity is not a religion, it’s a relationship.” Have you ever heard that phrase?

I’ve heard it countless times. To be fair, I used this phrase repeatedly in my previous life as a megachurch pastor. But since that time, I have also heard it from innumerable ex-Christians who carry feelings of shame and failure for having never achieved a “personal relationship with God” (or “personal relationship with Jesus”) in the way they were told it should work.

Be wary of shoulds.

Human beings must be more responsible with our language around the topic of religion, whether you believe in God or not. Let’s examine this phrase “personal relationship with God”, which is the crown jewel of Christianity.

This Substack newsletter is named “Deconstructionology”. The term deconstruction means to disassemble something into its separate parts and processes in order to understand it more insightfully. Our lives are governed by deeply-held beliefs, mindsets, narratives and ideologies that we rarely question or examine. We often find this to be true in the case of one’s learned religious beliefs, but it extends into virtually every domain of society and culture. It takes courageous to unshackle oneself from unhealthy and limiting beliefs.

Let’s deconstruct this idea of “personal relationship with God.” Let’s start with “personal relationship”. The below image captures it: two people, reciprocity.

A “personal relationship” is generally understood as a close, intimate connection between two individuals, characterized by emotional bonds and shared experiences. These relationships are built upon trust, intimacy, and mutual support, and can include family, friends, and romantic partners.

Key aspects of a personal relationship include:

Intimacy: Involves emotional closeness, vulnerability, and a sense of being known and accepted by the other person.

Commitment: Refers to the dedication and willingness to invest time and effort in nurturing the relationship.

Shared experiences: Involves mutual interests, hobbies, and the ability to engage in meaningful conversations and activities together.

Emotional support: Providing encouragement, understanding, and a sense of belonging to each other.

Respect: Valuing each other’s opinions, feelings, and boundaries.

The second part of the common Christian phrase, added to “personal relationship”, is “with God”. According to the language of Christianity, what I just described above (emotional closeness, meaningful conversations, belonging to each other, etc.) is not only possible but expected when it comes to a human being’s faith in God. A personal relationship with God, in many faiths, is a direct, intimate connection individuals experience with God. This is not viewed as a special occurrence, but a normative component of one’s daily religious life. This includes conversation with God and moments of deep emotional bonding through emanations of love.

I read the following, written from an online Christian life coach:

“How do you have a conversation with God? Start your conversation by saying, “Good morning, God!” Listen for how He responds. Tell God what's on your mind and heart today, and listen for His response. Tell God how you feel when you hear Him responding back to you. Tell God about something you're looking forward to doing, and listen for His response.”

We could more deeply deconstruct the notion of personal relationship by examining the idea of “interpersonal relationship” more extensively, and then apply these dynamics to how one expects to experience God. I’m not going to do that in this piece. I think you understand my point of what reasonably describes a “personal relationship”. The matter at hand is addressing this issue inside the claim that Christianity is not a religion but a personal relationship with God.

It’s important to note that this article is being written primarily for people who feel that religion failed them. If you have a “personal relationship with God” and it works perfectly for you, it’s all good. Perhaps you could read this article with an open mind toward those who did not have such an experience.

In my view, telling people that a person should relate and interact with “God” in the same way as two human beings is untrue, misleading and potentially damaging. I’m not saying there isn’t a meaningful sense of relationality associated with some people’s view of “God”. But the idea that the dynamics of an interpersonal relationship should define one’s faith in “God” is a lot to ask. The assumption is that the kind of relational intimacy, emotional support, shared experiences and two-way communication that characterize a healthy human relationship should be the norm for knowing God.

First consider that we cannot relate or interact with animals, stars, trees, or the sunset in the same way we do with our best friend or significant other. Right? Trees don’t listen, understand and reciprocate dialogue in human language. Dogs don’t understand the psychological and emotional dynamics of Homo sapiens. The sunset can’t offer personal guidance about specific life dilemmas.

I’m not saying that one’s connection with animals, trees, and sunsets are not deeply meaningful. I love my dogs, an avid naturalist, and sunsets are my escape. Animal Farm was my first read novel, I wept during Marley and Me, and was fascinated by The Secret Life of Trees, but none of this makes dogs, trees and sunsets human or capable of interpersonal human relationship.

Likewise, it seems patently obvious that an interpersonal relationship between two human beings cannot be replicated with an invisible entity such as “God”. And yet this idea is prevalent in Christianity, especially because God is presented as a supreme human-like being, portrayed through anthropomorphism in the Bible. We know a pig is not a human, but Animal Farm could make you think differently by projecting human-like qualities onto the pig. We know God is spirit, but the Bible could make you think otherwise by projecting human-like qualities onto God.

There’s a difference between saying that God is “personal” as opposed to God is a “person”. Many Christians are fond of the idea of a personal and relational God, and claim that an intimate relationship like we have with other people is possible.

Let’s dial it back a notch and consider ghosts. Generally, a ghost is the soul or spirit of a dead person that is believed by some people to be able to appear to the living. Let’s say you believe ghosts are real. Even if you did, I think you would concede that having a personal relationship with a ghost would not be like your relationship with your spouse, partner or best friend.

How Christianity frames “personal relationship with God” is confusing. It can include aspects of family, friendship and romantic relationships. At the very least it seems that a good Christian should be able to experience the following:

Interpersonal dialogue with God and the certainty that God is actively listening and speaking

Experiences of emotional bonding and intimacy where acceptance, understanding, belonging, care, love, empathy, tenderness and refuge are offered by God to the person

Expectation that given the nature of God who is perfect in every way, the personal relationship fully satisfies and completes the other person

I have a “Dear Jim” folder with scores of emails from people who express a sense of deep shame and failure that the above dynamics never seemed to happen for them. Inevitably, they blame themselves:

Do I not have enough faith?

Should I try harder?

Is something wrong with me?

Am I not good enough?

Is God displeased with me?

Is there sin or worldly desires in my life?

Adding insult to injury, these individuals often felt pressure to pretend like a personal relationship with God was happening.

Some Christians refer to God as “Papa God”, an informal or affectionate term for “father”. The term signifies God as a loving and nurturing father figure, similar to a child’s relationship with their own parent. It emphasizes God’s compassion, tenderness, and willingness to care for and guide individuals, akin to a father’s role.

However, if you pressed a person on how far one should take the “father” metaphor, they would likely concede that God cannot be a Gandalf-figure in the sky. Yet, these same people insist that one should be able to experience a fatherly relationship with “God”.

It should also be noted that the “father” metaphor is not a positive one for many people. The parent-child metaphor wouldn’t work for those who were victims of parental abuse, particularly by one’s father.

The above picture seems harmless. Right? But there’s a downside.

The phrase “Jesus is my boyfriend” is often used in Christianity to express a close, intimate, and loving relationship with Jesus, similar to how one might describe a romantic relationship. The language used in some worship songs and personal expressions of faith can be metaphorical, using human concepts like love, marriage, and intimacy to describe a spiritual connection with God.

Consider these worship song lyrics:

I feel your touch

I'm resting in the arms of God

I hang on to every word you say

You are closer, closer than my skin

I want to touch You, I want to see Your face

We are God’s lovers

To feel the warmth of your embrace

I love the way you hold me

Speak to me, I am listening, I am waiting

God you leave me breathless

Have your way in me lord

He is jealous for me

Lay back against you and breath, feel your heart beat

I recently read a couple Christian excerpts that likens a relationship with God with having a husband.

“There is a mutual resignation, or making over of their persons one to another. . . . Christ makes himself over to the soul, to be his, as to all the love, care, and tenderness of a husband; and the soul gives up itself wholly unto the Lord Christ, to be his, as to all loving, tender obedience.”

“So, I want to encourage you this week and next. Instead of wishing you had a husband who knew exactly what you were thinking and was able to anticipate your needs at any time, and instead of longing for someone whom you can depend on to always be there for you no matter what…here is a new strategy. What if you were to focus on your “spiritual husband.” Whether you’re married or not, if you know God, through a relationship with Jesus, you already have the perfect husband.”

I previously published a six-part series on the psychology of religion, which explores the psychological dynamics of belief in and experiences of God. There are several areas of note that come up in conversations such as this, including:

Religious experience - subjective experience which is interpreted within a religious framework.

Religious ecstasy - a state of altered consciousness characterized by an intense connection to a divine being, often accompanied by emotional euphoria and possibly physical sensations.

Mysticism - popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness, which is given a religious or spiritual meaning.

A useful book to explore the subject of religious experience further is, The Varieties Of Religious Experience: A Study In Human Nature. In my psychology of religion series I include several resources to explore these areas more extensively as you have interest.

Religious experiences are often expressed in poetic, symbolic, and metaphorical language. Sometimes these accounts can be confused by how literally a person might interpret them. My main intent on this point is simply to acknowledge that people have religious experiences. Unless these advocate hate, hostility or violence, it’s not my place to judge what experiences people claim to have and find meaningful. Our religious, spiritual or peak experiences are unique to each of us.

However, one should be careful about using their spiritual experience as a standard for others to follow. Unfortunately, Christians are prone to assume that everyone should be relating to God within the framework of a “personal relationship”. Religion tends to revere and reify the saints and mystics who spoke of having intense experiences of God. Teresa of Avila, Julian of Norwich and St. John of the Cross come to mind.

It is often conveyed that experiences of relationship with God is the litmus test for being a true Christian. The super-spiritual person is one who has mystical encounters with God, connects with God on the level of human emotions, routinely interacts with God conversationally, and has experiences of being held, loved, protected and comforted in the arms of God.

As a reminder, my point here is not to call into question any particular religious experience a person may have when they felt a deep spiritual and emotional connection and bond with God. In this article, I am especially considering the person for whom the idea of “personal relationship with God” never seemed to work.

Pathological Religious Relationships

The notion that it’s a positive attribute of Christianity that it’s “not a religion but a relationship” depends on who you ask. Though I’m not going to belabor this point here, it might be that Christianity would better off to actually accept that it is in fact a “religion” and drop the expectation that it function like an interpersonal relationship with God. I point this our because the idea of an interpersonal relationship with God requires the theistic view of God, which I consider to be quite harmful as typically taught.

I recently received an email that started like this:

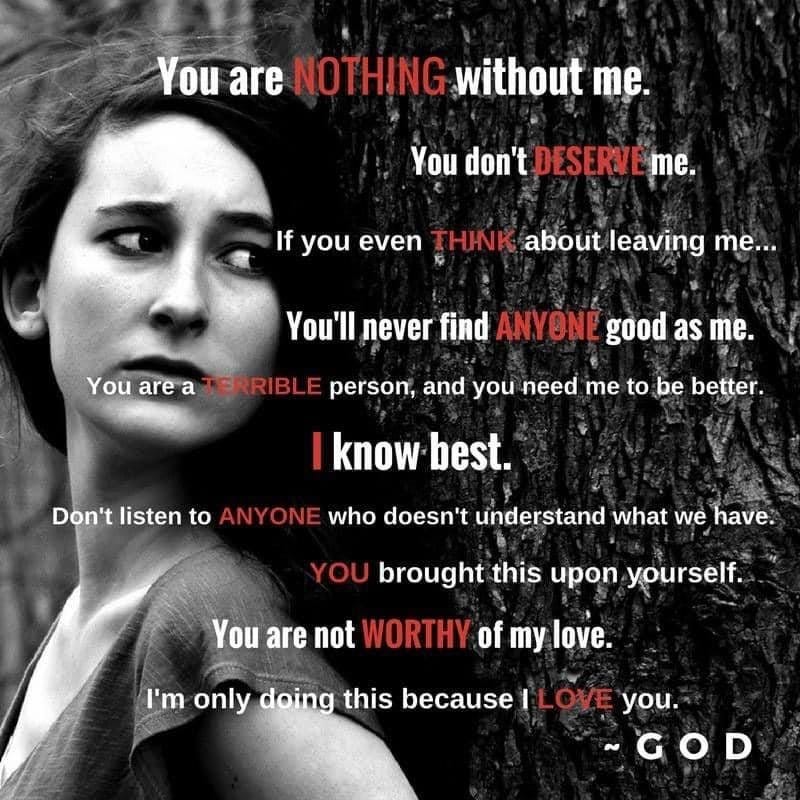

“My first abusive relationship was with God.”

For people who are traumatized by toxic religion, the relationship metaphor doesn’t translate. I wrote about this in my article, When You’re in an Abusive Relationship with God: Escaping Toxic Religion Codependency. For these individuals, even the word “love” does not work as they have learned that “love” is demanding, conditional, capricious and cruel.

Abusive, codependent and narcissistic relationships are toxic, and you often find these dynamics in toxic versions of “relationship with God.”

The warning signs of an abusive relationship typically include:

Controlling behavior

One of the fundamental signs of an abusive relationship is the abuser’s desire to have complete control over his victim’s life. The abuser may tell the other person whom she may see or be friends with, how she can dress, how she can act or speak, or may try to control any other aspect of her life. He may believe that the victim “belongs to him” and therefore he has the right to make decisions for her.

Jealousy and possessiveness

Another key sign of abuse is extreme, obsessive jealousy and persistent mistrust. The abuser may keep a close watch on the victim and interrogate her constantly about where she was, what she did, whom she spoke to, and so on; he may make accusations or fly into a rage for no good reason.

Misogyny

Male abusers often harbor negative feelings toward women in general. They may believe that women are inferior or unintelligent, or that a woman’s “proper” place is to be submissive and obedient.

Mood swings and short temper

Abusers are often easily angered, prone to becoming enraged over trivial matters. They may have sudden mood swings, violently angry one moment and loving and kind the next, a “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” personality. Victims of abuse often change their entire lives in an attempt to avoid making their abuser angry.

Threats, intimidation, and physical violence

The most certain sign of an abuser is the use of physical force or the threat of such force. Pushing, shoving, slapping, hitting, throwing or smashing objects, making threats to harm, or any other violent behavior or unwanted physical contact all qualify. Most abusers are also violent or cruel toward animals or children.

Emotional abuse and putdowns

Abuse can be verbal as well as physical. Abusers often insult their victims, call them names, make belittling comments, tell them that they are worthless, and generally attempt to make them feel miserable and inferior.

Blaming the victim

An abuser claims that the victim is responsible for his emotional state and the abuse he inflicts on her. He will attempt to make the victim feel guilty or tell her that the abuse is “her own fault” for making him angry.

Hypercritical nature/Unrealistic expectations

Abusers are often extremely critical of their victim’s appearance, lifestyle or preferences, and may explain away their constant criticism as being motivated by loving concern. They may have unrealistically high expectations, demanding that the victim meet all their physical and emotional needs perfectly all the time.

My point here is to represent the countless people I have worked with over the years who were indoctrinated into a toxic view of God that resembles an abusive relationship, commonly experienced by women particularly in scenarios of domestic violence.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Deconstructionology with Jim Palmer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.